Teens get summer crash course at 45th annual Governor’s School for Excellence

Here’s the scenario: It’s been a long, hard week, and soon you must present an in-depth analysis of a practically unsolvable social issue — to the governor, no less. Time is running out, the Big Guy is waiting, and you’ve barely had the chance to organize your thoughts, much less practice your delivery.

It’s a predicament that most reasonable humans would regard as a real-world nightmare. For 131 artistically and academically talented young Delaware high school students, it was more like a dream come true.

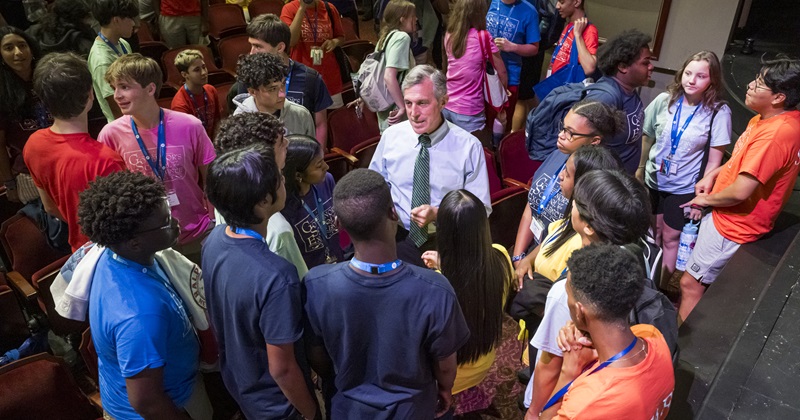

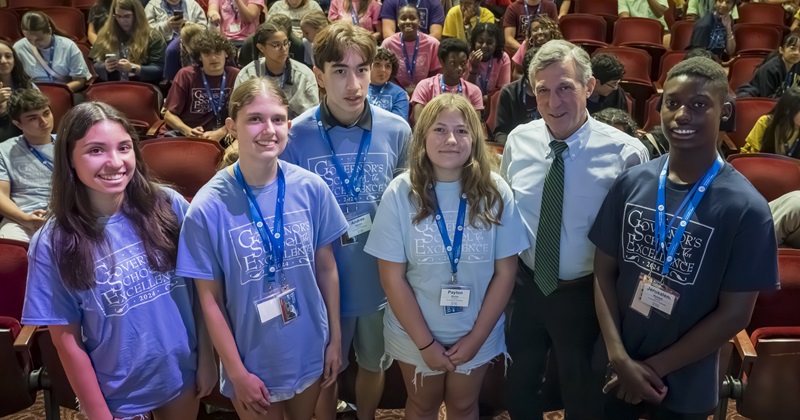

Soon after Delaware Gov. John Carney arrived on the University of Delaware campus for his annual get-together with the teens of the Governor’s School for Excellence, the seniors-to-be were more than ready to go toe-to-toe with one of Delaware’s most experienced politicians.

And he was here to listen.

Sadie Polk was so jazzed up after several days of college-level lessons that she didn’t even need her notes as she made her presentation to Carney at the 45th annual Governor’s School, sponsored by the office of the governor in cooperation with the Delaware Department of Education and UD’s Division of Professional and Continuing Studies (UD PCS).

Immediately, Polk launched a barrage of facts.

“Right now, one in eight Delawareans are food insecure. And even more worrying, one in five children are food insecure,” Polk, who attends Newark Charter School, told the governor. “Unfortunately, the people who are more food insecure also struggle with housing prices: Right now, 50,000 Delawareans are cost-burdened, and the people who are cost burdened often prioritize putting a roof over their head instead of putting food in their stomach.”

What can be done, she asked the governor — and what are you doing about it?

Carney countered quickly.

“One way to address that is on the income side,” he said. “For the first time I can remember, we have more jobs available than we do people looking for work. So, a couple years ago I signed a bill that would increase the minimum wage to $15 an hour,” yet preserve some food and housing subsidies.

But that subsidized support can be tenuous, he said.

“At some point as they make more money, they fall off the cliff with respect to eligibility, so we’ve been working on enhancing eligibility in our state,” he said. “This is a really important and complicated issue.”

And it wasn’t the only one he’d face. Soon, other sections of the class rose to pepper the governor with hard truths about similarly slippery issues — the opioid and fentanyl crisis, school safety, homelessness. Easy solutions wouldn’t be easily found today, but the true lessons had already been learned: College academics can be a pressure cooker, but it’s the kind of pressure that helps you grow.

A crash course on college life

The week’s topics were gut-check tough, leaning purposely toward science’s cutting edge: The students, who came to UD from 43 Delaware schools, got crash courses in kinesiology, artificial intelligence and marine sciences. Through class sessions and field trips, they were guided by faculty from the Joseph R. Biden, Jr. School of Public Policy and Administration, and the Colleges of Engineering, Health Sciences, Arts and Sciences, and Earth, Ocean and Environment.

Throughout, the competitive program embraced the same interdisciplinary approaches that are instilled in UD students. The teens worked problems as a college student would — by engaging with one another and stress-testing their ideas, guided all the while by energetic resident assistants who accompanied them on their weeklong stay in UD dorms.

“For sure there’s a lot of discussion that happens in the lectures,” said Rachel Durbano of Newark, who attends Sanford School and wants to attend UD as an English major. “Also, we have what are called the quads, which are groups of students paired with one of the resident assistants. Those students are drawn from all the programs, academic, theater, art and music and choir. So you get to interact with what other people are doing and have a chance to bond with a smaller group of people.”

Students were encouraged to confront some of the same political issues preoccupying the world today but also got the chance to explore less urgent conundrums, such as the censorship of rock lyrics and personal branding in the age of social media.

“On the first day, we had business and economics, and at our first lecture we played games that kind of simulated how the world creates money, which was really, really interesting, and it taught me a lot,” said Nirali Walekar of Caravel Academy. “All of the lectures and all of the activities that I had at the University were very engaging. And all of the professors were really, really good.”

The teens take on the housing crisis

Earlier in the week, one of those really good professors tried his best to prepare his students for the looming matchup with Carney, warning the class that they shouldn’t expect a governor to easily find local solutions to global problems.

“When you start to study public policy, you begin to understand that there are certain things that are tackled at different levels,” Biden School assistant professor Philip Barnes told the students. “Some issues you can tackle at the very local level. Some, like climate change, we really need to tackle internationally.”

Unless the governor is provided with custom-fit, Delaware-centric ideas, he may not be compelled to engage, Barnes warned. “He might throw the federal government under the bus.’’

He also cautioned them against viewing any problem in isolation, since most big issues come wrapped in a tangled interplay of cause and effect.

“Oftentimes, you’re going to find that there are things that are both cause and consequence,” he said. “It’s like a vicious cycle, right?”

So, they must dive deeper, into “causes of the causes,” all the way to the essence of the disparities. The sometimes-vague nature of reality also was called into question in another class, a half-day mega-session on artificial intelligence led by professors Kathleen McCoy and Keith Decker of the Department of Computer and Information Sciences.

In the age of AI, riddles remain

It was a class that gave the students some dizzying encounters with all sorts of startling mathematical creatures: One minute they were wading through stochastic Markovian processes, the next they were wandering along the unsteady pathways of Gödel’s incompleteness theorems. The professors took them all the way from the foreseeable future, back in time to the ancient Greeks, who gave AI researchers some of the foundations of logic that never seem to age.

By the end of the presentation, they had clearly learned many things, though these were the sort of university-level facts that seem to gleefully raise more questions than they answer. That’s especially true in artificial intelligence, a field driven by mathematics and logic, yet also vulnerable to the paradoxes and limitations inherent to those systems.

In other words, to fulfill AI’s potential and understand its challenges, scientists must start with the knowledge that some things cannot be known. In building a system resting on the foundations of logic, they must accept that those foundations can be shaky: In mathematics, it’s provably true that you cannot prove everything that’s actually true.

Well into the morning, the mind-boggling paradoxes persisted: They even learned that artificial intelligence isn’t always all that intelligent. In fact, it’s prone to the occasional fact-free response and “hallucinated content.”

“ChatGPT is actually really stupid,” McCoy told them. “It appears to act very smart. But at its heart, ChatGPT is simply predicting what’s the next word it should say given everything that it has seen so far. It doesn’t actually know any of the facts. It just knows the words,” so users should be watchful for bias.

After a week swimming in these academic depths, the students also sensed that they had gained more than just book knowledge. With the college application process looming, they now possessed a pair of résumé-boosting credentials: face time with a real governor and the elite achievement of being accepted to the Governor’s School itself.

“Being able to say I attended Governor’s School at UD, knowing that those college admissions people are aware of who that is, it’s definitely helpful,” Durbano said.

Another lesson came from the dean of the Graduate College and vice provost for graduate and professional education Lou Rossi, who told the students that they also had become part of a bigger family.

“I just want you to remember this about today: We’re not just any university. We’re your University, and you’re welcome here any time, even outside of Governor’s School,” he said.

For more information on the Delaware Governor’s School, visit www.pcs.udel.edu/govschool/